Hakkaisan Company Cafeteria. Minna no Shain Shokudo.

One of my favorite styles of food here is Japanese homestyle cooking. This way of cooking is rustic with limited ingredients and is usually very balanced and healthy. The best place I have found to enjoy Japanese homestyle cooking is the Hakkaisan Company Cafeteria. This building is called Minna no Shain Shokudo or “Employee Cafeteria for All”. This cafeteria is “for all” because it is open to employees and guests or visitors from outside the company, too. Anybody can stop by for lunch!

Employees can order breakfast, lunch or dinner any day. For visitors, the cafeteria is open to the public for lunch every day from 11am – 3pm.

Most often, you can find me at Minna no Shain Shokudo for lunch.

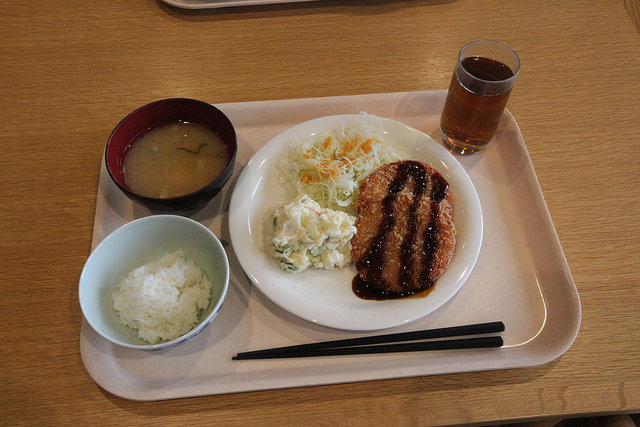

Typical Employee Lunch Tray at Minna no Shain Shokudo. Ham Katsu, Shredded Cabbage, Potato Salad, Koshihikari rice and Miso soup.

I sat down with Cafeteria Manager and Head Chef Mr. Sano to discuss the ins and outs of running a busy company cafeteria. Sano-san is tasked with a big challenge – for hungry brewers, he has to provide 3 meals a day, every day of the year (except New Years). During the brewing season, the sake mash does not take a rest, and neither do the brewers, so meals must be provided on weekends and holidays too. Every day sees as many 90 employees enjoy their breakfast, lunch or dinner at the cafeteria. Employees are served a simple buffet style meal that changes every day. Two constants every day are miso soup (with amazing in-house homemade miso) and delicious koshihikari rice (a prized local specialty). A word about Koshihikari rice – It is some of the best eating rice you’ll find anywhere and it grows all around this region. We are lucky to get to enjoy it every day with our meals. Please try it if you get the chance!

An example of the lunch set for guests visiting the Hakkaisan Company Cafeteria.

Guests visiting the Hakkaisan Company Cafeteria don’t eat the same lunch as the employees, but rather they enjoy a delicious set menu with a choice of meat or fish. This set for guests also includes the homemade miso soup and koshihikari rice. There are always a few seasonal sides along with salad and delicious homemade pickles, too. It is a fantastic home cooked lunch that draws people from far and wide. I see a lot of locals during the week and visitors from far and wide on the weekends. In the winter, I have also seen guests in their skiing gear grabbing lunch after a morning on the nearby slopes! If you visit us during lunchtime, you can enjoy lunch in the same room with the sake brewers! Please say hello!

Inside the cafeteria

So what’s on the menu for the brewers? Sample menus for employees include pork katsu with heaping sides of shredded cabbage and delicious salads on the side. Udon with homemade Tempura. Curry over rice with a side salad. And the employee’s favorite lunch? Sano-san tells me that is without a question karaage fried chicken tenderized with shiokoji, a salt and koji rice mixture. The karaage IS delicious but I’m team pork katsu when it comes to my favorite lunch.

Minna no Shain Shokudo Head Chef Mr. Sano.

You may be surprised to learn that there are some foods that are strictly off the menu at sake breweries. First is natto. For those who don’t know, natto is fermented soybeans with a slimey texture and strong smell that is much beloved by most Japanese. For sake brewers, eating this is forbidden as the microbes that ferment natto are powerful and could potentially interfere with the microbes of sake fermentation. Because of the strong odors, garlic is also avoided. Finally, Japanese mikan (kind of like a small orange) is also not allowed. The orange oil that is found in the mikan peel can get on your hands when peeling the mikan and it has antimicrobial properties which can inhibit fermentation.

Staying away from natto, garlic and mikan luckily leaves lots of leeway to have a great collection of dishes. If you are in Japan, a visit to the Hakkaisan Cafeteria is a wonderful way to spend a leisurely lunch – You’ll become a fan of Japanese homestyle cooking, too!

Koshihikari rice, a prized local specialty with local mountain vegetable Pickles!

The other method used to create depth of flavor and richness is aging and bottling this sake as a genshu. Most sake is diluted with water after production to bring the alcohol percentage usually down to about 15.5%. By contrast, genshu is a style of sake that is undiluted with water, similar in concept to “cask strength” products in the world of whiskey. In the case of Hakkaisan Snow-Aged Junmai Ginjo 3 Years, the alcohol percentage is 17%. What are the advantages of genshu? As genshu sakes are higher in alcohol, they offer more body, weight and structure to the sake. This translates into the ability to pair genshu sakes with non traditional foods. The keyword here is Umami! Richer foods with lots of savory characteristics pair beautifully with this genshu sake. Pairing ideas along this vein include beef tenderloin, Mediterranean seafood and even liver paté. This genshu sake also has the heft to stand up to mildly spicy dishes as well, so please try this sake with black pepper chicken or beef curry.

The other method used to create depth of flavor and richness is aging and bottling this sake as a genshu. Most sake is diluted with water after production to bring the alcohol percentage usually down to about 15.5%. By contrast, genshu is a style of sake that is undiluted with water, similar in concept to “cask strength” products in the world of whiskey. In the case of Hakkaisan Snow-Aged Junmai Ginjo 3 Years, the alcohol percentage is 17%. What are the advantages of genshu? As genshu sakes are higher in alcohol, they offer more body, weight and structure to the sake. This translates into the ability to pair genshu sakes with non traditional foods. The keyword here is Umami! Richer foods with lots of savory characteristics pair beautifully with this genshu sake. Pairing ideas along this vein include beef tenderloin, Mediterranean seafood and even liver paté. This genshu sake also has the heft to stand up to mildly spicy dishes as well, so please try this sake with black pepper chicken or beef curry.

Like so many things in Japanese culture, if you explore a little bit below the surface understanding of any topic, there is a whole world to discover… this is true for sushi, kimono and of course, sake, too.

Like so many things in Japanese culture, if you explore a little bit below the surface understanding of any topic, there is a whole world to discover… this is true for sushi, kimono and of course, sake, too.

The first step in making our own Shimenawa was to soften the rice straw to make it pliable. To this end, an an old fashioned press appeared from storage. this was a machine that looked like it had seen decades of Shimenawa production. A hand crank was turned and the rice fed through to crush it a bit and soften the fibers.

The first step in making our own Shimenawa was to soften the rice straw to make it pliable. To this end, an an old fashioned press appeared from storage. this was a machine that looked like it had seen decades of Shimenawa production. A hand crank was turned and the rice fed through to crush it a bit and soften the fibers.  After softening, the rice was brought into the work room and everyone sat down and started working. I first just watched and was amazed to see ropes and other woven decorations begin to appear.

After softening, the rice was brought into the work room and everyone sat down and started working. I first just watched and was amazed to see ropes and other woven decorations begin to appear. After a quick lesson, I was trying to make my own Shimenawa. My first two tries were a failure with my rope immediately unraveling, but after a bit more instruction, I figured out the trick and soon had a two ply thin rope of my own creation! I tied the rope into a circle to make a wreath.

After a quick lesson, I was trying to make my own Shimenawa. My first two tries were a failure with my rope immediately unraveling, but after a bit more instruction, I figured out the trick and soon had a two ply thin rope of my own creation! I tied the rope into a circle to make a wreath.

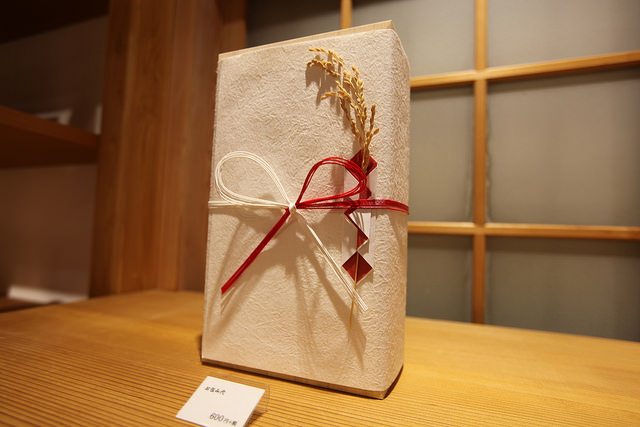

One of my favorite Japanese words that I’ve learned so far is gentei (限定), which simply means limited, but is often applied to a seasonal product or limited release product. Gentei items are popular in Japan! Hakkaisan also has some seasonal products, one of which is sold only in December each year.

One of my favorite Japanese words that I’ve learned so far is gentei (限定), which simply means limited, but is often applied to a seasonal product or limited release product. Gentei items are popular in Japan! Hakkaisan also has some seasonal products, one of which is sold only in December each year.

Almost every sake party or event I’ve been to in chilly Niigata has had someone assigned to be the Okanban. In short, the Okanban is the person in charge of warming sake. They make sure the sake is at the right temperature and ready when needed. At a busy event, it can be a lot to juggle, but a good Okanban keeps the sake and the party flowing!

Almost every sake party or event I’ve been to in chilly Niigata has had someone assigned to be the Okanban. In short, the Okanban is the person in charge of warming sake. They make sure the sake is at the right temperature and ready when needed. At a busy event, it can be a lot to juggle, but a good Okanban keeps the sake and the party flowing! The main tool of the okanban is the shukanki. This is a metal-lined wooden box that allows you to create a hot water bath inside for the sake carafes. A dial on the outside allows you to set the water temperature. This along with a good sake thermometer are what you need to get started.

The main tool of the okanban is the shukanki. This is a metal-lined wooden box that allows you to create a hot water bath inside for the sake carafes. A dial on the outside allows you to set the water temperature. This along with a good sake thermometer are what you need to get started.

After my arrival in Niigata, I was invited to visit the nearby Hakkaisan Son Jinja Shrine to join in a festival. The god of Hakkaisan Mountain is enshrined there and worshiped by locals. It sounded like a wonderful way to spend a fall afternoon. However, I started to worry a bit when I learned the festival was called “Hiwatari taisai “ or “walking on fire” festival.

After my arrival in Niigata, I was invited to visit the nearby Hakkaisan Son Jinja Shrine to join in a festival. The god of Hakkaisan Mountain is enshrined there and worshiped by locals. It sounded like a wonderful way to spend a fall afternoon. However, I started to worry a bit when I learned the festival was called “Hiwatari taisai “ or “walking on fire” festival.  I saw many festival goers walking around barefoot in preparation for the big event. After a beautiful procession of shinto priests, dignitaries and even an ogre (oni), the fire was lit. The flames were soon so high and the heat so intense that the crowd had to move back from the fence. When I saw the huge fire and billowing smoke, I began to question the sanity of the people lining up to walk on the coals, and I took a moment to re-confirm with myself that I would not be walking. When the fire died down, two paths were raked through the coals and sprinkled with salt to temper the heat.

I saw many festival goers walking around barefoot in preparation for the big event. After a beautiful procession of shinto priests, dignitaries and even an ogre (oni), the fire was lit. The flames were soon so high and the heat so intense that the crowd had to move back from the fence. When I saw the huge fire and billowing smoke, I began to question the sanity of the people lining up to walk on the coals, and I took a moment to re-confirm with myself that I would not be walking. When the fire died down, two paths were raked through the coals and sprinkled with salt to temper the heat.